New book: Effective Time Management: Using Microsoft Outlook to Organize Your Work and Personal Life

We’re excited to announce that Lothar Seiwert’s and Holger Woeltje’s Effective Time Management: Using Microsoft Outlook to Organize Your Work and Personal Life (ISBN 9780735660045; 272 pages) is now available for purchase!

You can find the book’s introduction in this previous post.

In today’s post, please enjoy reading an excerpt from Chapter 4, “How to Make Your Daily Planning Work in Real Life.”

Chapter 4 - How to Make Your Daily Planning Work in Real Life

“Things Always Turn Out Differently Anyway”

In this chapter, you will

· Learn the basics of successful day planning.

· Combine similar tasks into blocks.

· Use appointment lists.

· Fine-tune your day planner.

· Use the task bar in Outlook.

You have created your task list, have given the tasks a due date and prioritized them (see Chapter 2, "How to Work More Effectively with Tasks and Priorities"). You have planned your week with long-standing appointments and newly updated meetings as well as your “appointments with yourself” according to the Kiesel principle (“schedule big rocks first"; see Chapter 3, "How to Gain More Time for What’s Essential with an Effective Week Planner"). Confident and full of energy, you start your day—and then suddenly it’s evening already. You were able to keep most of the appointments, but the majority of the items on your task list have not been taken care of….

A Typical Day at Robin’s Office…

It’s already 9:26 A.M. when Robin Wood enters the conference room in a bad mood to begin his work day. Usually it’s fine to leave the house at 8:10 A.M., usually his commute to work will take exactly 50 minutes. But today one lane was closed due to landscaping—at this time of day, go figure!—and to make things worse, traffic was especially heavy…

“Sorry, I got stuck in rush-hour traffic,” he mumbles.

“Which is the same every morning at this time,” his boss replies with obviously little sympathy.

“But it’s really not my fault. This sort of thing just happens—especially to me. Why does it always happen to me and Fred, but hardly ever to the others?” Robin muses. At least his colleague Holly Holt greets him good-naturedly, and her smile cheers him up a bit. The next hours are proof, in his mind, that it’s impossible to plan your day well, no matter what: Once again, the meeting lasts an hour longer than scheduled. Afterwards he was going to finish the presentation for his talk at tomorrow’s trade show. But when he’s back at the computer, he first takes a “quick look” at the new email messages instead.

Forty-five minutes later, he is interrupted by a colleague who needs help with a problem. Of course, the phone doesn’t stop ringing. Suddenly he realizes that he has another meeting in 15 minutes. This meeting, however, takes place in a different building, and it takes him 20 minutes to get there, a fact he had not taken into consideration when glancing at the “3:30 P.M. meeting” request. At least this meeting ends on time, and on the way to get there he was able to grab something to eat at the hotdog stand—three hours past lunchtime.

Back at his desk, he could finally get started on the presentation—theoretically, anyway—but there are a few other things he should get done beforehand, so he’s trying to squeeze those in really quickly. After a while, he becomes aware of how quiet everything is around him. It can’t be past 6 P.M. already, can it? It sure can be. OK, let’s do this. Finally Robin starts designing a new slide. As this task begins to get tedious, he checks his Microsoft Outlook inbox and answers a few requests, which shouldn’t take too much time. Afterwards, he follows a couple of exciting links for special rental car offers. Oops! It’s 7:30 P.M. already. Robin realizes that he won’t finish the presentation today—at least not in the office. Oh, well. Who cares. Wouldn’t be the first time he’s taking work home… “So, what’s the point of planning? Things always turn out differently anyway!”

Not everything in life works out perfectly. Nevertheless, many people assume that things will always turn out as they had hoped, because more often than not, they actually turn out that way, which gives them room for more planning. Besides, there’s no fun in constantly assuming the worst. However, if you assume that what worked out perfectly without any glitches in record time with a lot of luck will continue to do so in the future, you shouldn't be disappointed or even surprised if it doesn’t work out quite so perfectly next time. Trying to halfway catch up on today’s completely impossible schedule of too many tight appointments by working overtime or by distributing tasks and appointments to the upcoming (and equally packed) days, while being totally stressed out, is even less fun than assuming that some things might go wrong or take a little longer.

You can protect yourself against some of the disturbances, interruptions, and distractions. You don’t need to let yourself get distracted by everything—but you can never completely turn off all distractions. These include unexpected chances and opportunities that really do require immediate action and are important enough to postpone other things. Reasonable daily planning is geared toward reality and takes such situations into consideration—within certain limits.

Realistic daily planning—or rather, its implementation, taking action accordingly—is a difficult and immense challenge. Hello, long-term plans and goals (and weekly planning): allow me to introduce you to the harsh reality of life. The challenge is to combine the two without getting lost in short-term distractions and all the exciting or urgent but unimportant stuff. Above all, you have to make consistent decisions to just say "No," and by doing so, say "Yes" to what really matters to you, your company, your boss, your clients, your family, and your friends. Really implementing your goals and B-tasks, putting your plan into action at the moment of choice, requires a large amount of self-discipline. At this point, time management either works out or fails.

The following often stand in the way of planning your day and implementing your plan—the top reasons why people fail:

· The desire to do everything at once.

· Delays, slip-ups, and things that “just go wrong.” (This happens occasionally, but you always have to plan for and be prepared for it to happen. Most people just assume that everything will always work out as planned.)

· Overestimation of your own capabilities or poor planning of time requirements.

· Only reacting, performing C-tasks first, failing to hold yourself accountable, being defensive and trying to blame someone else for your failures.

· Unexpected disruptions and interruptions, distractions, fluctuating levels of concentration.

· An acute aversion to some tasks, no self discipline, listlessness and “procrastinitis”: doing all the unimportant, easy, and fun D-tasks first, thus wasting time and procrastinating on the more difficult, sometimes boring or riskier, but much more important tasks.

Let’s Get Started and Change This!

For effective day planning you should take the following steps into consideration:

· Plan for delays, glitches, disruptions, and interruptions. They will happen, so try to prevent them, find a strategy to protect yourself against the ones you can avoid, and still leave some room to catch up with your work if some of them still happen.

· Concentrate on what’s essential, plan that first, and then take care of it consistently.

· Estimate the time requirements and your own performance realistically.

· Find a way to bundle the smaller tasks and leave free time slots in your plan as buffer zones .

· Tackle an issue and take responsibility, hold yourself accountable, and practice self-discipline to do boring and hard stuff when necessary to gain more time for tasks/activities that are fun afterwards, reach your goals, finish your work on time, and get home earlier (you can make a difference; see Chapter 7, "How to Truly Benefit from This Book").

Now that we have compiled the requirements of a solid schedule, it’s high time to get started with implementing it.

The Basics of Successful Day Planning

Build time blocks to pool similar tasks, and process them in a concentrated fashion in a single stretch (see the sidebar “What Is a Block?” in Chapter 1, “How Not to Drown in the Email Flood”). Learn to estimate the actual time requirement of a specific task correctly—many people try to rely on their intuition and come up with unrealistic values.

Use your daily performance curve in combination with your disruption curve (you'll learn about these later in this section) to figure out the best time of the day to isolate yourself against disruptions and to focus on the most important tasks of the day. Combine phone calls and minor daily tasks into categories, so you can perform them as a block or during waiting or idle times, and thus take optimal advantage of intervals between bigger tasks.

Combine Similar Tasks into Task Blocks

How much time do you waste with the little stuff? A “quick” phone call here, a “short” email message there, and before you know it, 20 minutes have gone by. You should combine such similar small tasks into task blocks.

Doing so has the following advantages:

· You will make faster headway, because you don’t need to get started again with a different kind of work every time (for example, when you switch to email from editing a report, you need two to three minutes to really get up to speed for answering messages. If you just answer one or two and then do something else, you’ll need the three minutes again when you come back to email). Working on ten five-minute phone calls or email messages at a stretch takes a lot less time than working on ten different email messages ten times in between other tasks. The effect is amplified by your ability to see the big picture. For example, you will automatically keep your phone calls short, if all the important issues have been addressed for that one call and you know that you still need to get eight more phone calls done within the next half hour.

· Unlike when you “just really quickly take care of some small task in between larger tasks,” creating blocks allows you to see exactly how many email messages you get done in 30 minutes or how long it takes you to make five short phone calls. If you watch yourself for a while, you can come up with a good average value that allows you to estimate the time requirements more realistically and thus plan more effectively. You will also have an easier time finding out in which areas it makes sense to optimize processes, cut reserved time shorter, or invest more time.

· If you schedule your blocks at approximately the same time each day, you also gain the additional benefits of a routine. The whole issue becomes a kind of ritual and gives your day a firm structure. Such recurrent actions at the same times of day have a positive effect on your work performance. They keep you grounded as you move through your day, and help you center yourself more quickly.

· You will find it easier to concentrate on your big, important tasks, and it also becomes easier to prevent distractions from items that you will later take care of in the block. For example, if you realize that it would be necessary to make a phone call, but it doesn't have to happen at this very moment, you just add it to the list. Therefore, you won’t be distracted for very long but can continue to concentrate on the task at hand.

Use Categories when Creating Blocks

Think about the areas for which you can create meaningful blocks. There are some tasks for which it makes sense to plan one or more blocks per day (for example, reading and answering email). For others, one to three blocks per week are sufficient, if not enough tasks accrue per day, if the tasks can wait a few days, or if you simply can’t take care of an issue every day. Certain blocks even make sense monthly or quarterly—for example, expense accounts.

Tip Add the Block suffix to the Outlook category name of each block building category (you'll learn more about block building toward the end of the chapter, in “Hide the Tasks Intended for Block Building in the Week/Day Views”). This is the most practical way to avoid frustration and other problems when you work with block building categories and want to use filters later.

Enter the names of the blocks that will come up more frequently—such as Calls (Block) for phone calls that are longer than three minutes—into your main category list (for more about working with categories, see Chapter 3). Now, if you think of a new task that you would like to mark for the next block, just press Ctrl+Shift+K, for example, to create a new task right from the middle of editing an email message. Enter the details (see Chapter 3) and assign the corresponding block, such as “Calls (Block)”, as category.

Whenever you need to—for your daily schedule, for example—you can then switch comfortably to a view that is sorted by category, collapse other categories, and filter the view by due date, to see your call block with all phone calls that must happen in the next five days, for example (see Figure 4-1). Setting the corresponding views is covered later in this chapter in “Order Must Prevail.”

Figure 4-1 With few mouse clicks, you can set the task list so you can only view the tasks which that are pending in the next few days for the corresponding block (group by category).

A Special Task Block: The ActionList

What to do with all the small items, which only take up to 10 minutes, max? Combine them into a special block under the “ActionList (Block)” category. This block is an exception in that you don’t work through it at a single stretch, because it includes diverse smaller issues from different areas. Instead, you always call it up when you have short idle times, for example, 10 minutes before the start of a meeting in the conference room or 8 minutes before an important phone appointment, when there is no other larger task you want to start yet. This way you can take care of these things quickly in between larger tasks and are filling short waiting or idle times.

Look the Truth in the Eye: Time Protocols

Keeping time protocols—or, more specifically, time use protocols—is a simple routine with a huge impact:

· After completing a task and keeping track of the time, you can estimate the time required for other tasks that come up in a similar way much more accurately.

· You will recognize individual issues and how much time they actually took you to accomplish—these values frequently differ slightly or even dramatically from the values you would have estimated. In combination with the creation of blocks, you might notice that “answering four short customer requests,” which you would have estimated to take at most 20 to 25 minutes, in reality took a whole hour.

· After a while, you can see quite clearly for which areas you need to allocate and plan for more time, and for which you can reduce the allotted time. You will recognize which tasks take most of your time and where it makes sense to investigate possible ways for optimizing your work.

Creating a time protocol is simple: Take a few very typical work days, and just track everything you are doing—everything that takes more than 10 minutes. If there are a few shorter tasks to perform, such as “8 min. for 3 short phone calls from ActionList,” you should protocol those as well. What’s important is that you always carry your time protocol with you, measure the time exactly, and enter everything immediately, as soon as it’s done. (You don’t need to run around with a stop watch, but you should take a look at your watch at the beginning and end of each task.) It’s up to you whether to record your time protocol on paper, enter it into Microsoft Excel Mobile on your smartphone, or use the journal function of Outlook with automatic time recording.

In the simplest version, you just enter the start and end time of the task and a detailed description (in other words, not just “call”). Exceptions are blocks with many small activities at a stretch, where a collective name is sufficient (such as “email block”). Details in a further column are always helpful; for example, “10 messages deleted immediately, 5 small ones answered quickly, and 3 large ones taken care of.” That’s enough in the beginning. The protocol becomes more meaningful (albeit more complex) if you prioritize the task according to the Eisenhower matrix (see Chapter 2); insert a column for the duration in minutes; in one column enter what you had planned for this time slot and in another column document your evaluation of this task (for example, “great: 100% correctly done as planned, but went much faster” or “wasn’t really necessary right now and took a lot of time”); or even record your physical or emotional state in yet another column (“tired and having a hard time concentrating,” “wide awake and very creative,” “still tired, but routine stuff going well and quickly”).

If your problem is procrastinating important tasks, getting easily distracted by other things, or fighting a lack of self-discipline, the time protocol can help you. If you look at your plan, see “write report for board meeting” but are entering something like “15 minutes spent aimlessly clicking around in the inbox,” instead, you will realize right there and then, while entering these remarks, that you are shirking the actual task. This should shake you awake and hopefully cause you to quit postponing this unpleasant but nevertheless very important task.

Keep a time protocol consistently for at least three, or preferably five, representative work days, and enter each task of 10 minutes or more. Even though it might not be a lot of fun, it’s worth it!

For Advanced Users: Take Advantage of the Journal for Semi-Automatic Time Protocols

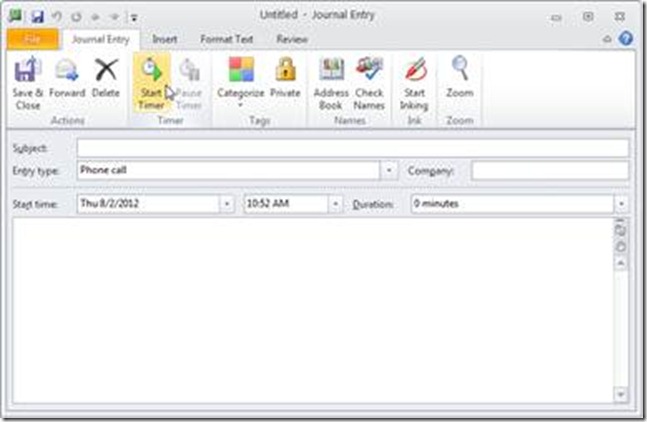

To save you from having to constantly switch between different applications and continuously look at your watch, the journal function of Outlook can help you create a time protocol (see Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2 The journal function of Outlook has automatic time recording that can help you with your time protocol.

Whenever you begin a new task, just use Alt+Tab to switch to a different Outlook window (press Tab again and release it while keeping Alt pressed and continue pressing Tab again until you have reached Outlook—unless Outlook is already open in the foreground). Then press Ctrl+Shift+J. Outlook will open a form for creating a journal entry that already contains the current date and time. Enter a unique subject. The Entry Type list contains all of the tasks that Outlook can automatically protocol. Ignore this field, because you can’t customize it by adding entries, and you’d therefore be too limited. Instead, click Categorize (or, in Outlook 2003, the Categories button in the lower-right corner) and select the appropriate categories from the list.

Then click the Start Timer button (or, in Microsoft Office Outlook 2003, press Alt+M). With Alt+Tab, you can switch back to the window that was open before you established the journal entry, while the journal window with activated time recording stays open. After you have finished the task, use Alt+Tab to move back to the open journal entry, and click Stop Timer (in Outlook 2003, just press Alt+M again). Outlook has now automatically added the duration. Enter any additional comments into the note field before saving and closing your journal entry. Because you probably won’t need the Company field for your time protocol, you can use it to note something else instead, such as the priority or your level of satisfaction with the completion of the task, so you can later sort for this criterion and use it for evaluation purposes. Here you can also add remarks about the project or the part of your life this current task belongs to (see Chapter 3).

To evaluate your daily protocol, switch to the Entry List view. The typical Timeline view of the journal might not be very practical when dealing with many short tasks instead of task blocks. You should therefore define a new view of the type Table, which you can arrange or group, for example, by category or duration, to see which of your tasks take the most time or which type/category of tasks you use the most time for. You can also write the journal entries into a Microsoft Excel file, to add up the time for further evaluation, create diagrams for a quick overview, and much more. To do this in Outlook 2010, select Options on the File tab and then, in theOutlookOptions dialog box, select Advanced. In the Export pane, click Export, and follow the instructions. In Outlook 2007/Outlook 2003, select ImportAnd Export from the File menu.

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](https://msdntnarchive.blob.core.windows.net/media/MSDNBlogsFS/prod.evol.blogs.msdn.com/CommunityServer.Blogs.Components.WeblogFiles/00/00/01/17/44/metablogapi/7673.clip_image0024_thumb_36209EED.jpg)