Implementing reliable messaging in distributed systems can be challenging. This article describes how to use the Transactional Outbox pattern for reliable messaging and guaranteed delivery of events, an important part of supporting idempotent message processing. To accomplish this, you'll use Azure Cosmos DB transactional batches and change feed in combination with Azure Service Bus.

Overview

Microservice architectures are becoming increasingly popular and show promise in solving problems like scalability, maintainability, and agility, especially in large applications. But this architectural pattern also introduces challenges when it comes to data handling. In distributed applications, each service independently maintains the data it needs to operate in a dedicated service-owned datastore. To support such a scenario, you typically use a messaging solution like RabbitMQ, Kafka, or Azure Service Bus that distributes data (events) from one service via a messaging bus to other services of the application. Internal or external consumers can then subscribe to those messages and get notified of changes as soon as data is manipulated.

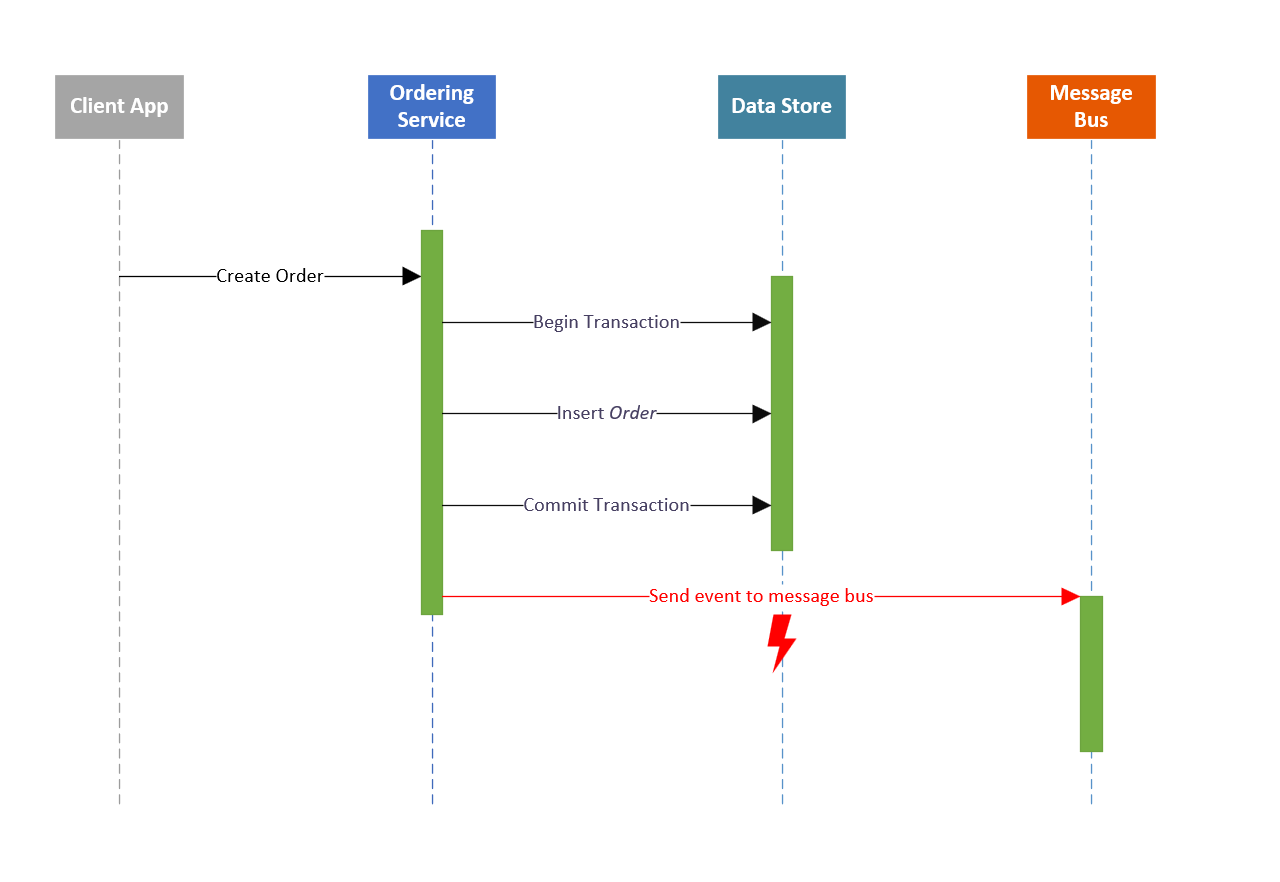

A well-known example in that area is an ordering system: when a user wants to create an order, an Ordering service receives data from a client application via a REST endpoint. It maps the payload to an internal representation of an Order object to validate the data. After a successful commit to the database, it publishes an OrderCreated event to a message bus. Any other service interested in new orders (for example an Inventory or Invoicing service), would subscribe to OrderCreated messages, process them, and store them in its own database.

The following pseudocode shows how this process typically looks from the Ordering service perspective:

CreateNewOrder(CreateOrderDto order){

// Validate the incoming data.

...

// Apply business logic.

...

// Save the object to the database.

var result = _orderRespository.Create(order);

// Publish the respective event.

_messagingService.Publish(new OrderCreatedEvent(result));

return Ok();

}

This approach works well until an error occurs between saving the order object and publishing the corresponding event. Sending an event might fail at this point for many reasons:

- Network errors

- Message service outage

- Host failure

Whatever the error is, the result is that the OrderCreated event can't be published to the message bus. Other services won't be notified that an order has been created. The Ordering service now has to take care of various things that don't relate to the actual business process. It needs to keep track of events that still need to be put on the message bus as soon as it's back online. Even the worst case can happen: data inconsistencies in the application because of lost events.

Solution

There's a well-known pattern called Transactional Outbox that can help you avoid these situations. It ensures events are saved in a datastore (typically in an Outbox table in your database) before they're ultimately pushed to a message broker. If the business object and the corresponding events are saved within the same database transaction, it's guaranteed that no data will be lost. Everything will be committed, or everything will roll back if there's an error. To eventually publish the event, a different service or worker process queries the Outbox table for unhandled entries, publishes the events, and marks them as processed. This pattern ensures events won't be lost after a business object is created or modified.

Download a Visio file of this architecture.

In a relational database, the implementation of the pattern is straightforward. If the service uses Entity Framework Core, for example, it will use an Entity Framework context to create a database transaction, save the business object and the event, and commit the transaction–or do a rollback. Also, the worker service that's processing events is easy to implement: it periodically queries the Outbox table for new entries, publishes newly inserted events to the message bus, and finally marks these entries as processed.

In practice, things aren't as easy as they might look at first. Most importantly, you need to make sure that the order of the events is preserved so that an OrderUpdated event doesn't get published before an OrderCreated event.

Implementation in Azure Cosmos DB

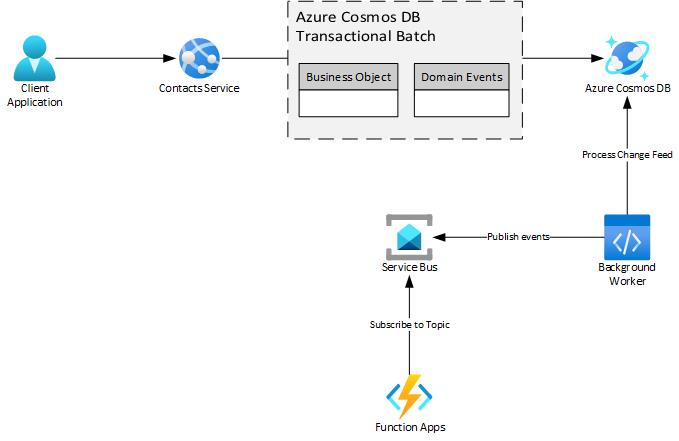

This section shows how to implement the Transactional Outbox pattern in Azure Cosmos DB to achieve reliable, in-order messaging between different services with the help of the Azure Cosmos DB change feed and Service Bus. It demonstrates a sample service that manages Contact objects (FirstName, LastName, Email, Company information, and so on). It uses the Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern and follows basic domain-driven design concepts. You can find the sample code for the implementation on GitHub.

A Contact object in the sample service has the following structure:

{

"name": {

"firstName": "John",

"lastName": "Doe"

},

"description": "This is a contact",

"email": "johndoe@contoso.com",

"company": {

"companyName": "Contoso",

"street": "Street",

"houseNumber": "1a",

"postalCode": "092821",

"city": "Palo Alto",

"country": "US"

},

"createdAt": "2021-09-22T11:07:37.3022907+02:00",

"deleted": false

}

As soon as a Contact is created or updated, it emits events that contain information about the current change. Among others, domain events can be:

ContactCreated. Raised when a contact is added.ContactNameUpdated. Raised whenFirstNameorLastNameis changed.ContactEmailUpdated. Raised when the email address is updated.ContactCompanyUpdated. Raised when any of the company properties are changed.

Transactional batches

To implement this pattern, you need to ensure the Contact business object and the corresponding events will be saved in the same database transaction. In Azure Cosmos DB, transactions work differently than they do in relational database systems. Azure Cosmos DB transactions, called transactional batches, operate on a single logical partition, so they guarantee Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability (ACID) properties. You can't save two documents in a transactional batch operation in different containers or logical partitions. For the sample service, that means that both the business object and the event or events will be put in the same container and logical partition.

Context, repositories, and UnitOfWork

The core of the sample implementation is a container context that keeps track of objects that are saved in the same transactional batch. It maintains a list of created and modified objects and operates on a single Azure Cosmos DB container. The interface for it looks like this:

public interface IContainerContext

{

public Container Container { get; }

public List<IDataObject<Entity>> DataObjects { get; }

public void Add(IDataObject<Entity> entity);

public Task<List<IDataObject<Entity>>> SaveChangesAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

public void Reset();

}

The list in the container context component tracks Contact and DomainEvent objects. Both will be put in the same container. That means multiple types of objects are stored in the same Azure Cosmos DB container and use a Type property to distinguish between a business object and an event.

For each type, there's a dedicated repository that defines and implements the data access. The Contact repository interface provides these methods:

public interface IContactsRepository

{

public void Create(Contact contact);

public Task<(Contact, string)> ReadAsync(Guid id, string etag);

public Task DeleteAsync(Guid id, string etag);

public Task<(List<(Contact, string)>, bool, string)> ReadAllAsync(int pageSize, string continuationToken);

public void Update(Contact contact, string etag);

}

The Event repository looks similar, except there's only one method, which creates new events in the store:

public interface IEventRepository

{

public void Create(ContactDomainEvent e);

}

The implementations of both repository interfaces get a reference via dependency injection to a single IContainerContext instance to ensure that both operate on the same Azure Cosmos DB context.

The last component is UnitOfWork, which commits the changes held in the IContainerContext instance to Azure Cosmos DB:

public class UnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork

{

private readonly IContainerContext _context;

public IContactRepository ContactsRepo { get; }

public UnitOfWork(IContainerContext ctx, IContactRepository cRepo)

{

_context = ctx;

ContactsRepo = cRepo;

}

public Task<List<IDataObject<Entity>>> CommitAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

return _context.SaveChangesAsync(cancellationToken);

}

}

Event handling: Creation and publication

Every time a Contact object is created, modified or (soft-) deleted, the service raises a corresponding event. The core of the solution provided is a combination of domain-driven design (DDD) and the mediator pattern proposed by Jimmy Bogard. He suggests maintaining a list of events that happened because of modifications of the domain object and publishing these events before you save the actual object to the database.

The list of changes is kept in the domain object itself so that no other component can modify the chain of events. The behavior of maintaining events (IEvent instances) in the domain object is defined via an interface IEventEmitter<IEvent> and implemented in an abstract DomainEntity class:

public abstract class DomainEntity : Entity, IEventEmitter<IEvent>

{

[...]

[...]

private readonly List<IEvent> _events = new();

[JsonIgnore] public IReadOnlyList<IEvent> DomainEvents => _events.AsReadOnly();

public virtual void AddEvent(IEvent domainEvent)

{

var i = _events.FindIndex(0, e => e.Action == domainEvent.Action);

if (i < 0)

{

_events.Add(domainEvent);

}

else

{

_events.RemoveAt(i);

_events.Insert(i, domainEvent);

}

}

[...]

[...]

}

The Contact object raises domain events. The Contact entity follows basic DDD concepts, configuring the domain properties' setters as private. No public setters exist in the class. Instead, it offers methods to manipulate the internal state. In these methods, appropriate events for a certain modification (for example ContactNameUpdated or ContactEmailUpdated) can be raised.

Here's an example for updates to the name of a contact. (The event is raised at the end of the method.)

public void SetName(string firstName, string lastName)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(firstName) ||

string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(lastName))

{

throw new ArgumentException("FirstName or LastName cannot be empty");

}

Name = new Name(firstName, lastName);

if (IsNew) return;

AddEvent(new ContactNameUpdatedEvent(Id, Name));

ModifiedAt = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow;

}

The corresponding ContactNameUpdatedEvent, which tracks the changes, looks like this:

public class ContactNameUpdatedEvent : ContactDomainEvent

{

public Name Name { get; }

public ContactNameUpdatedEvent(Guid contactId, Name contactName) :

base(Guid.NewGuid(), contactId, nameof(ContactNameUpdatedEvent))

{

Name = contactName;

}

}

So far, events are just logged in the domain object and nothing is saved to the database or even published to a message broker. Following the recommendation, the list of events will be processed right before the business object is saved to the data store. In this case, it happens in the SaveChangesAsync method of the IContainerContext instance, which is implemented in a private RaiseDomainEvents method. (dObjs is the list of tracked entities of the container context.)

private void RaiseDomainEvents(List<IDataObject<Entity>> dObjs)

{

var eventEmitters = new List<IEventEmitter<IEvent>>();

// Get all EventEmitters.

foreach (var o in dObjs)

if (o.Data is IEventEmitter<IEvent> ee)

eventEmitters.Add(ee);

// Raise events.

if (eventEmitters.Count <= 0) return;

foreach (var evt in eventEmitters.SelectMany(eventEmitter => eventEmitter.DomainEvents))

_mediator.Publish(evt);

}

On the last line, the MediatR package, an implementation of the mediator pattern in C#, is used to publish an event within the application. Doing so is possible because all events like ContactNameUpdatedEvent implement the INotification interface of the MediatR package.

These events need to be processed by a corresponding handler. Here, the IEventsRepository implementation comes into play. Here's the sample of the NameUpdated event handler:

public class ContactNameUpdatedHandler :

INotificationHandler<ContactNameUpdatedEvent>

{

private IEventRepository EventRepository { get; }

public ContactNameUpdatedHandler(IEventRepository eventRepo)

{

EventRepository = eventRepo;

}

public Task Handle(ContactNameUpdatedEvent notification,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

EventRepository.Create(notification);

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}

An IEventRepository instance is injected into the handler class via the constructor. As soon as a ContactNameUpdatedEvent is published in the service, the Handle method is invoked and uses the events repository instance to create a notification object. That notification object in turn is inserted in the list of tracked objects in the IContainerContext object and joins the objects that are saved in the same transactional batch to Azure Cosmos DB.

So far, the container context knows which objects to process. To eventually persist the tracked objects to Azure Cosmos DB, the IContainerContext implementation creates the transactional batch, adds all relevant objects, and runs the operation against the database. The process described is handled in the SaveInTransactionalBatchAsync method, which is invoked by the SaveChangesAsync method.

Here are the important parts of the implementation that you need to create and run the transactional batch:

private async Task<List<IDataObject<Entity>>> SaveInTransactionalBatchAsync(

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

if (DataObjects.Count > 0)

{

var pk = new PartitionKey(DataObjects[0].PartitionKey);

var tb = Container.CreateTransactionalBatch(pk);

DataObjects.ForEach(o =>

{

TransactionalBatchItemRequestOptions tro = null;

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(o.Etag))

tro = new TransactionalBatchItemRequestOptions { IfMatchEtag = o.Etag };

switch (o.State)

{

case EntityState.Created:

tb.CreateItem(o);

break;

case EntityState.Updated or EntityState.Deleted:

tb.ReplaceItem(o.Id, o, tro);

break;

}

});

var tbResult = await tb.ExecuteAsync(cancellationToken);

...

[Check for return codes, etc.]

...

}

// Return copy of current list as result.

var result = new List<IDataObject<Entity>>(DataObjects);

// Work has been successfully done. Reset DataObjects list.

DataObjects.Clear();

return result;

}

Here's an overview of how the process works so far (for updating the name on a contact object):

- A client wants to update the name of a contact. The

SetNamemethod is invoked on the contact object and the properties are updated. - The

ContactNameUpdatedevent is added to the list of events in the domain object. - The contact repository's

Updatemethod is invoked, which adds the domain object to the container context. The object is now tracked. CommitAsyncis invoked on theUnitOfWorkinstance, which in turn callsSaveChangesAsyncon the container context.- Within

SaveChangesAsync, all events in the list of the domain object are published by aMediatRinstance and are added via the event repository to the same container context. - In

SaveChangesAsync, aTransactionalBatchis created. It will hold both the contact object and the event. - The

TransactionalBatchruns and the data is committed to Azure Cosmos DB. SaveChangesAsyncandCommitAsyncsuccessfully return.

Persistence

As you can see in the preceding code snippets, all objects saved to Azure Cosmos DB are wrapped in a DataObject instance. This object provides common properties:

ID.PartitionKey.Type.State. LikeCreated,Updatedwon't be persisted in Azure Cosmos DB.Etag. For optimistic locking.TTL. Time To Live property for automatic cleanup of old documents.Data. Generic data object.

These properties are defined in a generic interface that's called IDataObject and is used by the repositories and the container context:

public interface IDataObject<out T> where T : Entity

{

string Id { get; }

string PartitionKey { get; }

string Type { get; }

T Data { get; }

string Etag { get; set; }

int Ttl { get; }

EntityState State { get; set; }

}

Objects wrapped in a DataObject instance and saved to the database will then look like this sample (Contact and ContactNameUpdatedEvent):

// Contact document/object. After creation.

{

"id": "b5e2e7aa-4982-4735-9422-c39a7c4af5c2",

"partitionKey": "b5e2e7aa-4982-4735-9422-c39a7c4af5c2",

"type": "contact",

"data": {

"name": {

"firstName": "John",

"lastName": "Doe"

},

"description": "This is a contact",

"email": "johndoe@contoso.com",

"company": {

"companyName": "Contoso",

"street": "Street",

"houseNumber": "1a",

"postalCode": "092821",

"city": "Palo Alto",

"country": "US"

},

"createdAt": "2021-09-22T11:07:37.3022907+02:00",

"deleted": false,

"id": "b5e2e7aa-4982-4735-9422-c39a7c4af5c2"

},

"ttl": -1,

"_etag": "\"180014cc-0000-1500-0000-614455330000\"",

"_ts": 1632301657

}

// After setting a new name, this is how an event document looks.

{

"id": "d6a5f4b2-84c3-4ac7-ae22-6f4025ba9ca0",

"partitionKey": "b5e2e7aa-4982-4735-9422-c39a7c4af5c2",

"type": "domainEvent",

"data": {

"name": {

"firstName": "Jane",

"lastName": "Doe"

},

"contactId": "b5e2e7aa-4982-4735-9422-c39a7c4af5c2",

"action": "ContactNameUpdatedEvent",

"id": "d6a5f4b2-84c3-4ac7-ae22-6f4025ba9ca0",

"createdAt": "2021-09-22T11:37:37.3022907+02:00"

},

"ttl": 120,

"_etag": "\"18005bce-0000-1500-0000-614456b80000\"",

"_ts": 1632303457

}

You can see that the Contact and ContactNameUpdatedEvent (type domainEvent) documents have the same partition key and that both documents will be persisted in the same logical partition.

Change feed processing

To read the stream of events and send them to a message broker, the service will use the Azure Cosmos DB change feed.

The change feed is a persistent log of changes in your container. It operates in the background and tracks modifications. Within one logical partition, the order of the changes is guaranteed. The most convenient way to read the change feed is to use an Azure function with an Azure Cosmos DB trigger. Another option is to use the change feed processor library. It lets you integrate change feed processing in your Web API as a background service (via the IHostedService interface). The sample here uses a simple console application that implements the abstract class BackgroundService to host long-running background tasks in .NET Core applications.

To receive the changes from the Azure Cosmos DB change feed, you need to instantiate a ChangeFeedProcessor object, register a handler method for message processing, and start listening for changes:

private async Task<ChangeFeedProcessor> StartChangeFeedProcessorAsync()

{

var changeFeedProcessor = _container

.GetChangeFeedProcessorBuilder<ExpandoObject>(

_configuration.GetSection("Cosmos")["ProcessorName"],

HandleChangesAsync)

.WithInstanceName(Environment.MachineName)

.WithLeaseContainer(_leaseContainer)

.WithMaxItems(25)

.WithStartTime(new DateTime(2000, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, DateTimeKind.Utc))

.WithPollInterval(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(3))

.Build();

_logger.LogInformation("Starting Change Feed Processor...");

await changeFeedProcessor.StartAsync();

_logger.LogInformation("Change Feed Processor started. Waiting for new messages to arrive.");

return changeFeedProcessor;

}

A handler method (HandleChangesAsync here) then processes the messages. In this sample, events are published to a Service Bus topic that's partitioned for scalability and has the de-duplication feature enabled. Any service interested in changes to Contact objects can then subscribe to that Service Bus topic and receive and process the changes for its own context.

The Service Bus messages produced have a SessionId property. When you use sessions in Service Bus, you guarantee that the order of the messages is preserved (FIFO). Preserving the order is necessary for this use case.

Here's the snippet that handles messages from the change feed:

private async Task HandleChangesAsync(IReadOnlyCollection<ExpandoObject> changes, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_logger.LogInformation($"Received {changes.Count} document(s).");

var eventsCount = 0;

Dictionary<string, List<ServiceBusMessage>> partitionedMessages = new();

foreach (var document in changes as dynamic)

{

if (!((IDictionary<string, object>)document).ContainsKey("type") ||

!((IDictionary<string, object>)document).ContainsKey("data")) continue; // Unknown document type.

if (document.type == EVENT_TYPE) // domainEvent.

{

string json = JsonConvert.SerializeObject(document.data);

var sbMessage = new ServiceBusMessage(json)

{

ContentType = "application/json",

Subject = document.data.action,

MessageId = document.id,

PartitionKey = document.partitionKey,

SessionId = document.partitionKey

};

// Create message batch per partitionKey.

if (partitionedMessages.ContainsKey(document.partitionKey))

{

partitionedMessages[sbMessage.PartitionKey].Add(sbMessage);

}

else

{

partitionedMessages[sbMessage.PartitionKey] = new List<ServiceBusMessage> { sbMessage };

}

eventsCount++;

}

}

if (partitionedMessages.Count > 0)

{

_logger.LogInformation($"Processing {eventsCount} event(s) in {partitionedMessages.Count} partition(s).");

// Loop over each partition.

foreach (var partition in partitionedMessages)

{

// Create batch for partition.

using var messageBatch =

await _topicSender.CreateMessageBatchAsync(cancellationToken);

foreach (var msg in partition.Value)

if (!messageBatch.TryAddMessage(msg))

throw new Exception();

_logger.LogInformation(

$"Sending {messageBatch.Count} event(s) to Service Bus. PartitionId: {partition.Key}");

try

{

await _topicSender.SendMessagesAsync(messageBatch, cancellationToken);

}

catch (Exception e)

{

_logger.LogError(e.Message);

throw;

}

}

}

else

{

_logger.LogInformation("No event documents in change feed batch. Waiting for new messages to arrive.");

}

}

Error handling

If there's an error while the changes are being processed, the change feed library will restart reading messages at the position where it successfully processed the last batch. For example, if the application successfully processed 10,000 messages, is now working on batch 10,001 to 10,025, and an error happens, it can restart and pick up its work at position 10,001. The library automatically tracks what has been processed via information saved in a Leases container in Azure Cosmos DB.

It's possible that the service will have already sent some of the messages that are reprocessed to Service Bus. Normally, that scenario would lead to duplicate message processing. As noted earlier, Service Bus has a feature for duplicate message detection that you need to enable for this scenario. The service checks if a message has already been added to a Service Bus topic (or queue) based on the application-controlled MessageId property of the message. That property is set to the ID of the event document. If the same message is sent again to Service Bus, the service will ignore and drop it.

Housekeeping

In a typical Transactional Outbox implementation, the service updates the handled events and sets a Processed property to true, indicating that a message has been successfully published. This behavior could be implemented manually in the handler method. In the current scenario, there's no need for such a process. Azure Cosmos DB tracks events that were processed by using the change feed (in combination with the Leases container).

As a last step, you occasionally need to delete the events from the container so that you keep only the most recent records/documents. To periodically do a cleanup, the implementation applies another feature of Azure Cosmos DB: Time To Live (TTL) on documents. Azure Cosmos DB can automatically delete documents based on a TTL property that can be added to a document: a time span in seconds. The service will constantly check the container for documents that have a TTL property. As soon as a document expires, Azure Cosmos DB will remove it from the database.

When all the components work as expected, events are processed and published quickly: within seconds. If there's an error in Azure Cosmos DB, events won't be sent to the message bus, because both the business object and the corresponding events can't be saved to the database. The only thing to consider is to set an appropriate TTL value on the DomainEvent documents when the background worker (change feed processor) or the service bus aren't available. In a production environment, it's best to pick a time span of multiple days. For example, 10 days. All components involved will then have enough time to process/publish changes within the application.

Summary

The Transactional Outbox pattern solves the problem of reliably publishing domain events in distributed systems. By committing the business object's state and its events in the same transactional batch and using a background processor as a message relay, you ensure that other services, internal or external, will eventually receive the information they depend on. This sample isn't a traditional implementation of the Transactional Outbox pattern. It uses features like the Azure Cosmos DB change feed and Time To Live that keep things simple and clean.

Here's a summary of the Azure components used in this scenario:

Download a Visio file of this architecture.

The advantages of this solution are:

- Reliable messaging and guaranteed delivery of events.

- Preserved order of events and message de-duplication via Service Bus.

- No need to maintain an extra

Processedproperty that indicates successful processing of an event document. - Deletion of events from Azure Cosmos DB via TTL. The process doesn't consume request units that are needed for handling user/application requests. Instead, it uses "leftover" request units in a background task.

- Error-proof processing of messages via

ChangeFeedProcessor(or an Azure function). - Optional: Multiple change feed processors, each maintaining its own pointer in the change feed.

Considerations

The sample application discussed in this article demonstrates how you can implement the Transactional Outbox pattern on Azure with Azure Cosmos DB and Service Bus. There are also other approaches that use NoSQL databases. To guarantee that the business object and events will be reliably saved in the database, you can embed the list of events in the business object document. The downside of this approach is that the cleanup process will need to update each document that contains events. That's not ideal, especially in terms of Request Unit cost, as compared to using TTL.

Keep in mind that you shouldn't consider the sample code provided here production-ready code. It has some limitations regarding multithreading, especially the way events are handled in the DomainEntity class and how objects are tracked in the CosmosContainerContext implementations. Use it as a starting point for your own implementations. Alternatively, consider using existing libraries that already have this functionality built into them like NServiceBus or MassTransit.

Deploy this scenario

You can find the source code, deployment files, and instructions to test this scenario on GitHub: https://github.com/mspnp/transactional-outbox-pattern.

Contributors

This article is maintained by Microsoft. It was originally written by the following contributors.

Principal author:

- Christian Dennig | Senior Software Engineer

To see non-public LinkedIn profiles, sign in to LinkedIn.

Next steps

Review these articles to learn more:

- Domain-driven design

- Azure Service Bus: Message de-duplication

- Change feed processor library

- Jimmy Bogard: A better domain events pattern