Events

Apr 8, 3 PM - May 28, 7 AM

Sharpen your AI skills and enter the sweepstakes to win a free Certification exam

Register now!This browser is no longer supported.

Upgrade to Microsoft Edge to take advantage of the latest features, security updates, and technical support.

Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Windows monthly quality updates are cumulative, containing all previously released fixes to ensure consistency and simplicity. For an operating system platform like Windows, which stays in support for multiple years, the size of monthly quality updates can quickly grow large, thus directly impacting network bandwidth consumption.

Today, this problem is addressed by using express downloads, where differential downloads for every changed file in the update are generated based on selected historical revisions plus the base version. In this paper, we introduce a new technique to build compact software update packages that are applicable to any revision of the base version, and then describe how Windows quality updates use this technique.

The following general terms apply throughout this document:

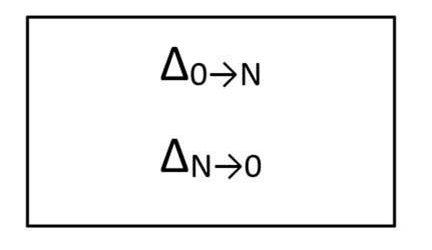

In this paper, we introduce a new technique that can produce compact software updates optimized for any origin/destination revision pair. It does this by calculating forward the differential of a changed file from the base version and its reverse differential back to the base version. Both forward and reverse differentials are then packaged as an update and distributed to the endpoints running the software to be updated. The update package contents can be symbolized as follows:

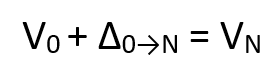

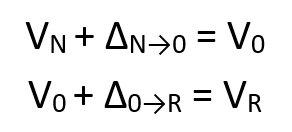

The endpoints that have the base version of the file (V0) hydrate the target revision (VN) by applying a simple transformation:

The endpoints that have revision N of the file (VN), hydrate the target revision (VR) by applying the following set of transformations:

The endpoints retain the reverse differentials for the software revision they are on, so that it can be used for hydrating and applying next revision update.

By using a common baseline, this technique produces a single update package with numerous advantages:

Historically, download sizes of Windows quality updates (Windows 10, version 1803 and older supported versions of Windows 10) were optimized by using express download. Express download is optimized such that updating Windows systems download the minimum number of bytes. This is achieved by generating differentials for every updated file based on selected historical base revisions of the same file + its base or RTM version.

For example, if the October monthly quality update has updated Notepad.exe, differentials for Notepad.exe file changes from September to October, August to October, July to October, June to October, and from the original feature release to October are generated. All these differentials are stored in a Patch Storage File (PSF, also referred to as express download files) and hosted or cached on Windows Update or other update management or distribution servers (for example, Windows Server Update Services (WSUS), Microsoft Configuration Manager, or a non-Microsoft update management or distribution server that supports express updates). A device applying express updates uses network protocol to determine optimal differentials, then downloads only what is needed from the update distribution endpoints.

The flip side of express download is that the size of PSF files can be large depending on the number of historical baselines against which differentials were calculated. Downloading and caching large PSF files to on-premises or remote update distribution servers is problematic for most organizations, hence they're unable to use express updates to keep their fleet of devices running Windows up to date. Secondly, due to the complexity of generating differentials and size of the express files that need to be cached on update distribution servers, it's only feasible to generate express download files for the most common baselines, thus express updates are only applicable to selected baselines. Finally, calculation of optimal differentials is expensive in terms of system memory utilization, especially for low-cost systems, impacting their ability to download and apply an update seamlessly.

In the following sections, we describe how quality updates use this technique based on forward and reverse differentials for newer releases of Windows and Windows Server to overcome the challenges with express downloads.

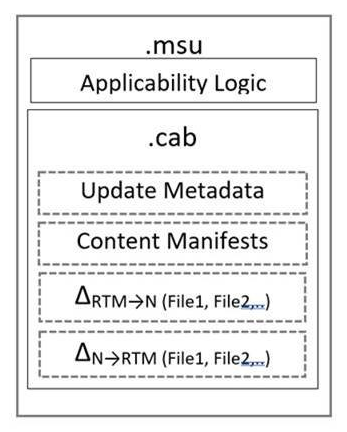

Windows quality update packages contain forward differentials from quality update RTM baselines (∆RTM→N) and reverse differentials back to RTM (∆N→RTM) for each file that has changed since RTM. By using the RTM version as the baseline, we ensure that all devices have an identical payload. Update package metadata, content manifests, and forward and reverse differentials are packaged into a cabinet file (.cab). This .cab file, and the applicability logic, will also be wrapped in Microsoft Standalone Update (.msu) format.

There can be cases where new files are added to the system during servicing. These files won't have RTM baselines, thus forward and reverse differentials can't be used. In these scenarios, null differentials are used to handle servicing. Null differentials are the slightly compressed and optimized version of the full binaries. Update packages can have either forward or reverse differentials, or null differential of any given binary in them. The following image symbolizes the content of a Windows quality update installer:

Once the usual applicability checks are performed on the update package and are determined to be applicable, the Windows component servicing infrastructure hydrates the full files during preinstallation and then proceeds with the usual installation process.

Below is a high-level sequence of activities that the component servicing infrastructure runs in a transaction to complete installation of the update:

f folder) and reverse differentials (under r folder) or null compressed files (under n folder) in the component store (%windir%\WinSxS folder).To ensure resiliency against component store corruption or missing files that could occur due to susceptibility of certain types of hardware to file system corruption, a corruption repair service has been traditionally used to recover the component store automatically (automatic corruption repair) or on demand (manual corruption repair) using an online or local repair source. This service will continue to offer the ability to repair and recover content for hydration and successfully install an update, if needed.

When corruption is detected during update operations, automatic corruption repair starts as usual and uses the Baseless Patch Storage File published to Windows Update for each update to fix corrupted manifests, binary differentials, or hydrated or full files. Baseless patch storage files contain reverse and forward differentials and full files for each updated component. Integrity of the repair files will be hash verified.

Corruption repair uses the component manifest to detect missing files and get hashes for corruption detection. During update installation, new registry flags for each differential staged on the machine are set. When automatic corruption repair runs, it scans hydrated files using the manifest and differential files using the flags. If the differential can't be found or verified, it's added to the list of corruptions to repair.

"Lazy automatic corruption repair" runs during update operations to detect corrupted binaries and differentials. While applying an update, if hydration of any file fails, "lazy" automatic corruption repair automatically starts, identifies the corrupted binary or differential file, and then adds it to the corruption list. Later, the update operation continues as far as it can go, so that "lazy" automatic corruption repair can collect as many corrupted files to fix as possible. At the end of the hydration section, the update fails, and automatic corruption repair starts. Automatic corruption repair runs as usual and at the end of its operation, adds the corruption list generated by "lazy" automatic corruption repair on top of the new list to repair. Automatic corruption repair then repairs the files on the corruption list and installation of the update will succeed on the next attempt.

Events

Apr 8, 3 PM - May 28, 7 AM

Sharpen your AI skills and enter the sweepstakes to win a free Certification exam

Register now!